…and what to do about it

By Jutta Treviranus

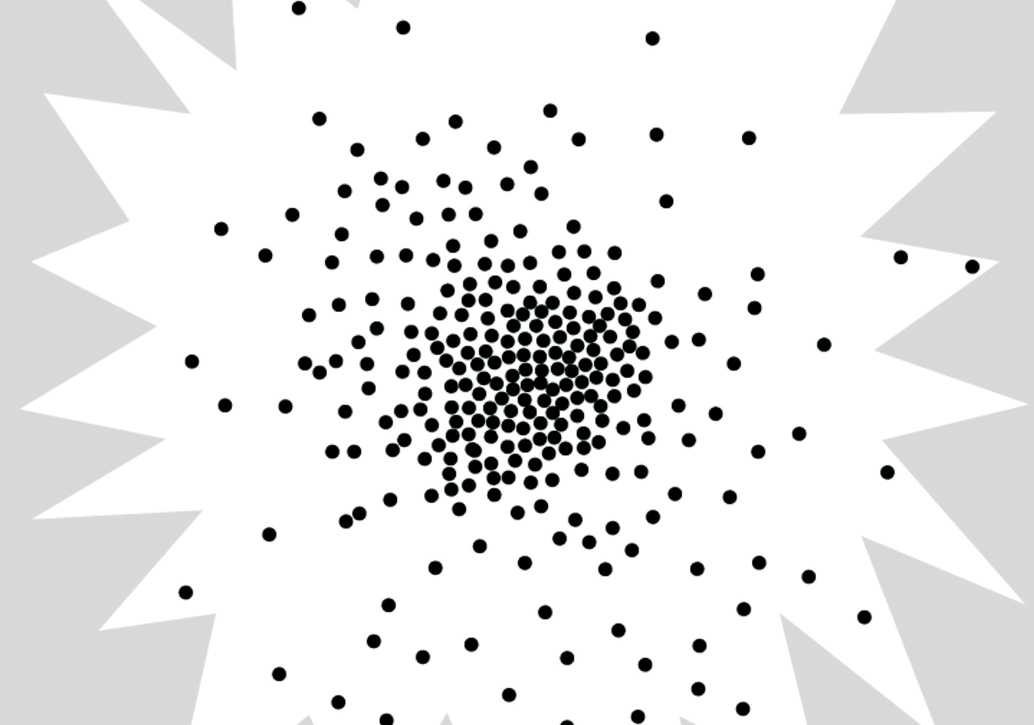

If we take any population of people and plot their needs and characteristics on a three-dimensional scatterplot, the plot will resemble a starburst. In that starburst, most dots will cluster in a denser centre while others spread out from the central core. There will be an invisible line some distance from the centre where people can be identified as having a disability.

Mainstream products, services, schools, places of employment, homes, communities and technologies are all, by default, designed for the denser cluster in the centre of the starburst.

Find yourself out at the periphery and it is likely that most things will not be made with your needs in mind. If something is made specifically for you—such as a computer keyboard that you can control, clothing you can put on, a kitchen or bathroom in which you can reach things, or learning material in a language you can understand—then it will not be as readily available, or as easy to set up or maintain. If what you are using needs to interoperate or work with products designed for the central core, such as software, it will not do this very well or consistently.

Most significantly, and despite the fact that your expectations regarding interoperability, availability and reliability will need to be lower, products that work for you (e.g., a Braille-equipped computer, a car that can fit your wheelchair or a bathtub you can get into) will probably cost up to 10 times more than mainstream products. This is largely because the manufacturer cannot take advantage of the lowering cost of mass production. Unfortunately, the high price tag for specialist products and services is one factor that leads to people with disabilities living below the poverty line.

Similar but different

Similar but different

One of the things to note about the dots on the starburst is that those in the central cluster are close together, with those on the periphery becoming further apart. This illustrates the fact that people with disabilities are more different from each other than those served by mainstream designs. Despite this, people at the periphery are often lumped together as one group and expected to be served by a single “accessible version.” As you can imagine, this one-size-fits-all approach to accessibility is problematic. It means that everyone with a disability has to live with a compromised fit, with fewer degrees of freedom to adapt to a design that does not work.

Another flawed approach is to cluster people into categories based on their medical diagnosis, even though there are many other factors that can influence an individual’s needs (e.g., the presence of a parent or spouse, place of residence). In addition, “medical diagnosis” does not always provide useful information about what I require—for example, if the category I am relegated to is “blind,” you will not know if I am Braille literate, have some residual vision, am an English language learner or can hear speech at standard volumes.

One size fits one

One size fits one

Humans and human societies are not comfortable with change. All of our systems of valuation, evidence and prioritization are based on the large numbers and average dominant patterns. This is especially true of our institutions, such as schools and governments, because they are built for stability. Markets are faster to respond, but markets have yet to recognize the business advantage of stretching to include people with disabilities. However, there is an emerging realization that people are diverse; that there are alternatives to mass manufacturing and marketing that recognize this human variability; and that we all benefit from a better personal fit. To create markets and services that recognize variations and do not leave people stranded at the periphery of the scatterplot, we need systems that can provide one-size-fits-one designs. One such approach is called AccessForAll, which is supported by an international standard (ISO/IEC 24751). AccessForAll was first implemented in Canada in two projects (Web4All, and TILE), but is now the basis of several other international projects, including FLOE, Cloud4All, Prosperity4All and APCP. As networks become more sophisticated and inclusive (whether based on local networks, the web, cloud services or cooperative platforms—similar to Airbnb or UBER, but with bottom-up governance and revenue models) and we recognize that we do not need to treat people as either a mass or those who do not fit, it becomes possible to create a society that does not leave people stranded at the edge of the starburst that is our human family.

Jutta Treviranus is the director of the Inclusive Design Research Centre in Toronto, Canada. She heads the Inclusive Design Institute, directs an innovative graduate program in Inclusive Design and is a professor at the OCAD University in Toronto. Jutta is also co-founder of Raising the Floor (RtF-I), a not-for-profit association based in Geneva, Switzerland, that is dedicated to making the web and mobile technologies accessible to those with disabilities and literacy and aging-related challenges, regardless of their economic status. RtF-I is responsible for leading the development of the GPII and advancing the concept of one-size-fits-one digital inclusion.

Jutta Treviranus is the director of the Inclusive Design Research Centre in Toronto, Canada. She heads the Inclusive Design Institute, directs an innovative graduate program in Inclusive Design and is a professor at the OCAD University in Toronto. Jutta is also co-founder of Raising the Floor (RtF-I), a not-for-profit association based in Geneva, Switzerland, that is dedicated to making the web and mobile technologies accessible to those with disabilities and literacy and aging-related challenges, regardless of their economic status. RtF-I is responsible for leading the development of the GPII and advancing the concept of one-size-fits-one digital inclusion.