Ethical considerations when families collude to withhold health information

By Karen E. Faith, BSW, MEd, MSC

Mrs. G is a 76-year-old widow who is receiving care in a rehabilitation facility after suffering a stroke that has left her paralyzed on the right side. With some speech pathology support, Mrs. G is able to communicate through simple “yes” and “no” responses and can write some words with her left hand.

Her family strongly believe that Mrs. G must be protected from any emotional or psychological distress. According to Mrs. G’s family, this belief is tied to their cultural and religious background. Her family is expressing their devotion to her by shielding her from the devastating news about her poor prognosis and the truth about her serious cardiovascular problems. At the family’s insistence, Mrs. G’s physician requests a physiotherapy assessment to determine her ability to participate in rehabilitation therapy, with the goal of helping her to walk again.

During her assessment of Mrs. G, the PT realizes that her patient has little or no understanding of her health picture. Mrs. G indicates to the PT that she is in a rehabilitation setting to rest up after being sick. Mrs. G communicates to the PT that she wishes to get up and walk so she can go home and resume to her daily activities. The PT is strongly suspecting that given how compromised Mrs. G is from the stroke that the goal for her to walk again and live independently is not realistic. More concerning is Mrs. G’s serious cardiovascular problems. The PT feels very distressed that this patient has little or no understanding of the gravity of her condition and the implications this has for her future health challenges and appropriate care options.

Competing obligations

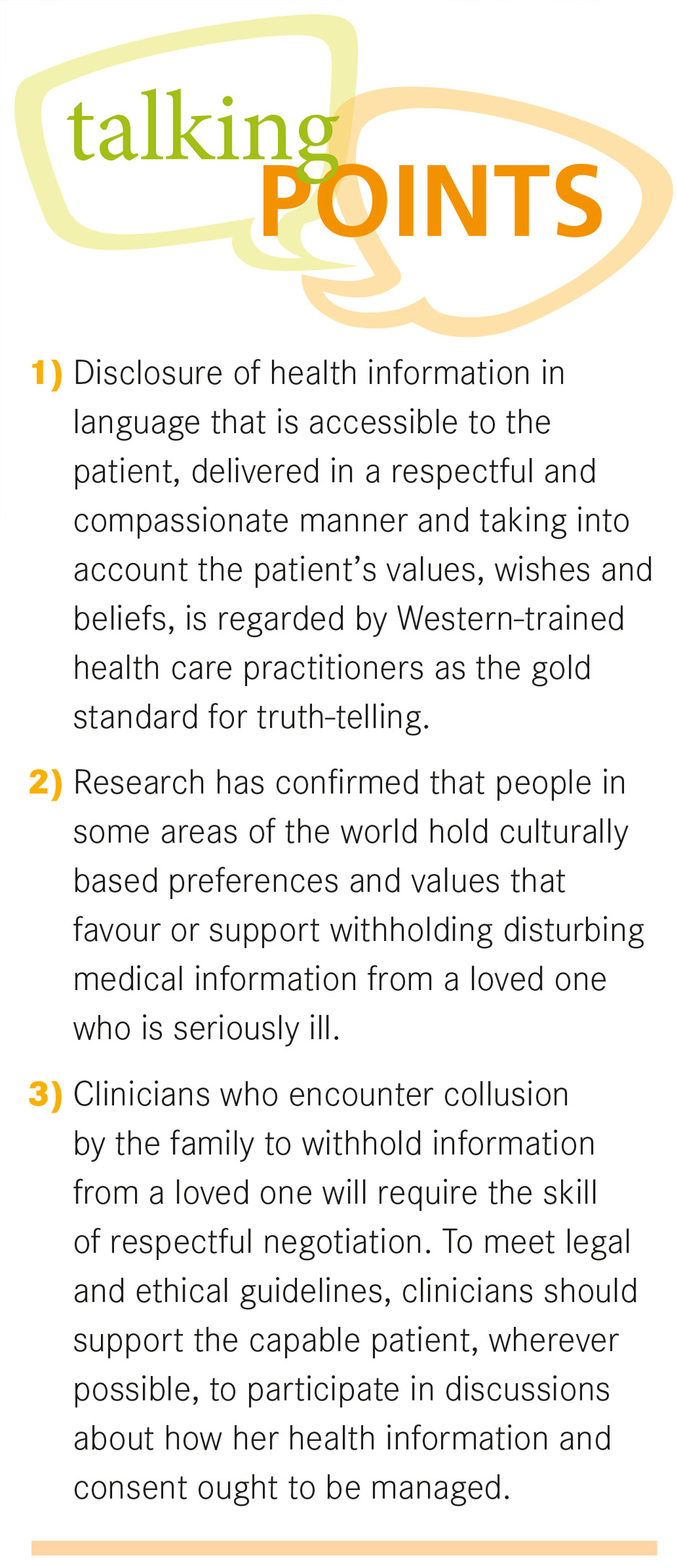

In Western societies, the matter of truth-telling is tied to the pre-eminent ethical principle of autonomy—i.e., the right of a person to make an informed decision regarding their own health and well-being based on the medical information provided to them by a clinician. However, Western notions concerning the obligation to disclose accurate medical information to patients, or truth-telling, are not universally shared. Research has confirmed that attitudes on this issue vary across the globe. People in some areas of the world hold culturally based preferences and values that favour or support withholding disturbing medical information from a loved one who is seriously ill.

Health care consent laws such as those that exist in Canada require that patients are provided with pertinent and accurate health information in order to make informed decisions about consent to treatment. Disclosure of health information in language that is accessible to the patient, delivered in a respectful and compassionate manner and taking into account the patient’s values, wishes and beliefs, is regarded by Western-trained health care practitioners as the gold standard for truth-telling. According to Rosenberg and colleagues: “Over time, physicians realized that nondisclosure rarely benefitted patients and, in some cases, caused harm.”

The moral compass on such an issue would seem to direct health care professionals to disclose medical information to all patients, were it not for the competing obligation to also respect the cultural and religious values of the patient and her family. In the case of Mrs. G, we can imagine the ethical tensions her care providers face in ensuring that her autonomy rights are respected while her familial values and beliefs are accommodated. The ethical challenge in cases like Mrs. G is centred on meeting one’s ethical and professional obligations regarding disclosure of health information and obtaining informed consent from a capable patient, while at the same time respecting the family’s wish to protect her from receiving information that they perceive as harmful to her. A family’s wish to protect a loved one in this manner is often an expression of how the family understands love, support and protection from harm within their own system of beliefs and values. Patients like Mrs. G are frequently aware that they are seriously ill, but collude with the family by never requesting their medical information.

respecting the family’s wish to protect her from receiving information that they perceive as harmful to her. A family’s wish to protect a loved one in this manner is often an expression of how the family understands love, support and protection from harm within their own system of beliefs and values. Patients like Mrs. G are frequently aware that they are seriously ill, but collude with the family by never requesting their medical information.

Key considerations

According to a study conducted by Kirschner and colleagues, truth-telling is one of many ethical challenges faced by rehabilitation clinicians in clinical practice.In addressing key elements of an ethical dilemma a clinician needs to consider legal guidelines, professional values and ethical principles to help answer the following: What should be done in this situation? Why should this action be taken or this particular decision made? And, subsequently, how should this action or decision be carried out, given the unique circumstances of the case in question? (Adapted from a definition of an ethical dilemma developed by Dr. B. Secker, University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics.)

The literature on ethics and truth-telling highlights some key considerations for health care providers in cases such as these. Clinicians should endeavour to understand the values, systems of beliefs and experiences that are leading the family to withhold health information from the patient. Demonstrating patience and curiosity can help to open an important dialogue in which family members are encouraged to share their worries and fears. Similarly, clinicians need to share what troubles them about the family’s collusion in withholding information; this is likely to include concerns that the care provider’s legal and professional obligations are not being upheld. It is imperative for clinicians to know at what point legal or ethical obligations are being seriously compromised and to obtain the appropriate legal and/or ethics advice. Skills of negotiation and conflict resolution are needed to help avoid or reduce confrontation. These challenging situations often benefit from the involvement of other members of the inter-professional team, such as social workers, bioethics consultants or chaplains.

Patient capability

Consistent with the principle of autonomy, the capable patient in situations such as these should, as far as possible, be supported in participating in discussions about her health information and consent to treatment. Health care providers should emphasize that Mrs. G’s capable wishes must remain a primary focus. Therefore, the question of whether Mrs. G agrees that her family should receive her health information needs to be explored respectfully, and ideally with her family present so that she can express her wishes to them. A supportive bedside discussion that engages both the family and Mrs. G in determining how her health information and consent for treatment will be managed is an important step in such negotiations.

Of course, a capable patient such as Mrs. G may elect to have all her health information given to her family and for her family to decide on the best course of action. This decision ought to be made voluntarily by the patient, without coercion from the family. In such cases, it is essential to advise the patient and her family that the patient can change her mind about this at any time, and that she should tell a member of the interprofessional team if this happens. Mrs. G and her family should be informed that, in accordance with existing laws and ethical principles governing health care, a patient’s direct request for her own health information will be honoured by an appropriate member of the health care team.

This case is a hypothetical one for illustrative purposes only.

Karen Faith BSW, MEd, MSc, is a bioethics consultant, writer, public speaker and member of the Joint Centre for Bioethics at the University of Toronto. She has served on the staff of the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and currently works with regional and community-based health care organizations.